Our second interview with one of the virtual concert creators is with Ken Adamson. In addition to recording and playing in the KCO, you can hear his recording as Sonolux on Soundcloud.

- KCO: Who are you what started you down your musical road?

- KCO: How did you end up in the orchestra?

- KCO: How did you get involved with the virtual projects broadly speaking?

- KCO: How long does it take to mix and master the audio for a video and how long does it take to master a concert?

- KCO: In a project like this, what is something that people just don’t expect?

KCO: Who are you what started you down your musical road?

Ken: I’m Ken Adamson and I play French horn. I play French horn now, but I didn’t always play French horn.

I started playing an instrument in the fourth grade. It would have been recorder or something like that, but they moved you off to another instrument pretty quickly. My dad was a clarinet player and was into the Dixieland Jazz-style clarinet. We grew up in Louisiana so it was a given and so that was what I played all the way through high school.

For my last two years in high school marching band, I played mellophone because who are we kidding, clarinets are useless in the marching band and I wanted to play something a little bit more flashy.

The band director said we need mellophones. Here’s a fingering chart and instrument. He had to show me some more. He was a trumpet player, so I got some private lessons from him.

I didn’t pick up the French horn until college. I thought that it would be pretty similar to mellophone or trumpet. Turns out, it’s much harder. Had I known, I might have picked a different instrument to switch to, but it was sort of opportunistic.

I went to college on a partial music scholarship for clarinet. The idea of switching instruments was a big deal. I would have needed to re-audition. But, the way that I came to playing French horn, it was a bit of a boondoggle.

KCO: What school was this?

Ken: That’s at Northwestern State University, at Natchitoches Louisiana, Central Louisiana. It’s a pretty decent, but unheard of, music program. The music program is almost a quarter of the school. It’s well funded by athletics. We were at all the games and everything.

You have to audition for every ensemble. The only thing that was a near guarantee was marching band. Even then, the section leaders required you to play some scales and learn the fight song. Not a full audition, but they make sure that you can actually play. You don’t have to be good, just be able to play.

They didn’t have as many ensemble choices in the fall, so that they didn’t compete too heavily with marching band. I don’t know where you hail from, but in the South, marching band is a big deal.

KCO: I went to school in New England and, you’re right, not as big a deal.

Ken: I was playing mellophone in marching band. I was going to my private, mandated clarinet lesson because I was a music major at that point. My clarinet teacher gave me the audition materials for fall wind ensemble. Show up and you do your audition on clarinet.

I show up and there’s a hundred clarinet players. Wind ensemble is going to take 12. But I really want to play in this thing. I’m listening to these people practice and we’ve got upper classmen that are virtuosic. I realized that I’m so out-classed there’s no chance that I’m going to be in this group. One of my new friends told me that she, “was the only person auditioning on bass clarinet. They need two bass clarinet players. Have you ever played bass clarinet? “

I played bass clarinet in high school. Using her instrument and materials, I basically sight-read the audition. I was the only other person to audition so I got in.

That was in the morning. That same afternoon the mellophone section leader from the marching band comes to me and asks, “do you play a concert horn?” I said no, not really. He handed me his horn and asked for some scales. I got some scales out and he said, “okay, well, your fingerings are wrong, this is double horn.” He actually had to show me some fingerings, and I went and I auditioned. I think there were 10 people auditioning for fall wind ensemble. I didn’t make it on horn. But with only 10 people, it wasn’t as long a shot at getting in on B-flat clarinet. But I did, I did wind up getting in the next spring.

KCO: This is your freshman year?

Ken: My freshman year, yes. I stuck with clarinet for another couple of months, so still going to my clarinet lesson, while playing in wind ensemble on bass clarinet, and marching band on mellophone. I dropped it entirely the next semester. I don’t know how they let me keep my scholarship. They should have made me re-audition on French horn, but maybe shoddy record-keeping?

The other interesting thing, at some point, I actually became a liberal arts major. I had a pretty shotgun set of focuses and among them was music. The other ones were actually engineering, math, and physics, which is the other half of my other major.

As time went on, that grew. My advisor asked if I knew anything about computers? I knew a lot about computers. She said that I really should think about computer science. That’s going to be a hot field and this in ‘93 or ‘94.

KCO: That’s some good advice though.

Ken: And it led me to Kirkland Civic Orchestra, by way of Microsoft Orchestra.

KCO: How did you end up in the orchestra?

Ken: It turns out that there’s a heavy overlap between tech and music. Every place I’ve worked, there’s been other people around me that play an instrument. When I was working for Microsoft, someone told me that Microsoft had an orchestra. That surprised me but I decided to check it out.

I went to Christmas concert in 2007 or 2008. I just watched. Hey, they’re not bad and they only have three French horns. But I chickened out. I could have joined and finished out the season but I waited close to a year and joined later in the season. I didn’t join early enough to play the first fall concert but in time to participate in the Christmas concert. I remember the first piece of music that I saw on a stand was Babes in Toyland. I just sat down where I thought the horns might be. The seating wasn’t that organized. I remember people start filtering in and it turns out that I just helped myself to the first horn part. Everybody in the horn section was like, that’s fine. I realized the error of my ways. By the second rehearsal, I said, “I’ll play another part.”

KCO: How did you get involved with the virtual projects broadly speaking?

Ken: Flash forward a few years. I’ve left Microsoft and I’m working at Getty Images. I meet a guy who is similarly a musician and a software engineer. He has a side business/hobby as recording engineer: recording, mixing, mastering–basically audio engineering as a whole.

I had been doing a little bit of that essentially remastering projects from the orchestra and from another concert band that I’m in. I started asking him questions and he said you just need to come over to my house and see my studio.

He took me under his wing and taught me quite a bit. That was around 2012, 2013. During one summer, I worked with him for a good six months or so. In the fall, I made the proposition to Jim, to let me handle recording. Jim does so much and that is one thing I could take that off his plate.

The recording part wasn’t a stretch for me because I had done a lot of that in college. There was a nice recording studio there. Our recital hall was fully mic’d and so I did quite a bit of practice on my own because I had keys to that stuff. When I was a student, I had jobs all over the music department.

I’d go in late at night and make copies of the master tapes and practice mixing on tape copies. I was somewhat familiar with the process but all analog. It’s a totally different world, when you’re about digital recording. A lot of the metaphors are still the same. We still use the same software as the 90s. Pro Tools was starting to be the predominant software even then.

The mixer behind me? That’s basically the same mixer that I learned on in college. The Mackie, 32 channel mixer, and I still use it. There’s a lot to be said for working in the analog domain for sound and muscle memory.

KCO: Using a mouse and even a touch screen, it’s just not the same thing.

Ken: It’s not. There’s nothing like a real, physical piece of equipment to work with that responds and has its own character. It’s like an instrument. If you’re already a musician, working with a piece of analog gear is a lot like playing an instrument itself.

Mixing and recording for the orchestra makes me the natural candidate for mixing audio in the virtual recordings, but I wasn’t originally tapped to do it. Dave was going to handle all of it. At the last minute, I was said why don’t you let me mix the audio. He was very appreciative, and I’ve had a had a great time doing it.

KCO: They sound good to me.

Ken: I treat them like a studio recording. It’s a little different when you’re recording the orchestra live. You have, essentially, a pre-mixed sound that you’re trying to capture. We’re fortunate in that, where we perform, in the chapel at Northwest University, has great acoustics. Getting a good stereo live recording is not a problem.

By contrast, when you have each individual part being sent to you in a video, I can treat them like studio recording. I do as much technically as I can to help the sound and help out the player. There’s a fairly intense editing process that is the same as with any studio recording: getting everybody in time, in tune, and still trying to preserve our sound. I think I’ve been reasonably successful with that.

KCO: Your skill level has increased over time. If I go back and listen to some of older the recordings, the newer ones are better.

Ken: Some of that is different techniques and better equipment, but I don’t want to deep dive and get too geeky about it. The KCO, we’ve just been getting better. I’ve been surprised at how much better that we’ve been getting over time. We’re also tackling harder and harder repertoire. Having a better sounding orchestra helps me move to techniques that you use for a better sounding orchestra. They go hand in hand.

KCO: How long does it take to mix and master the audio for a video and how long does it take to master a concert?

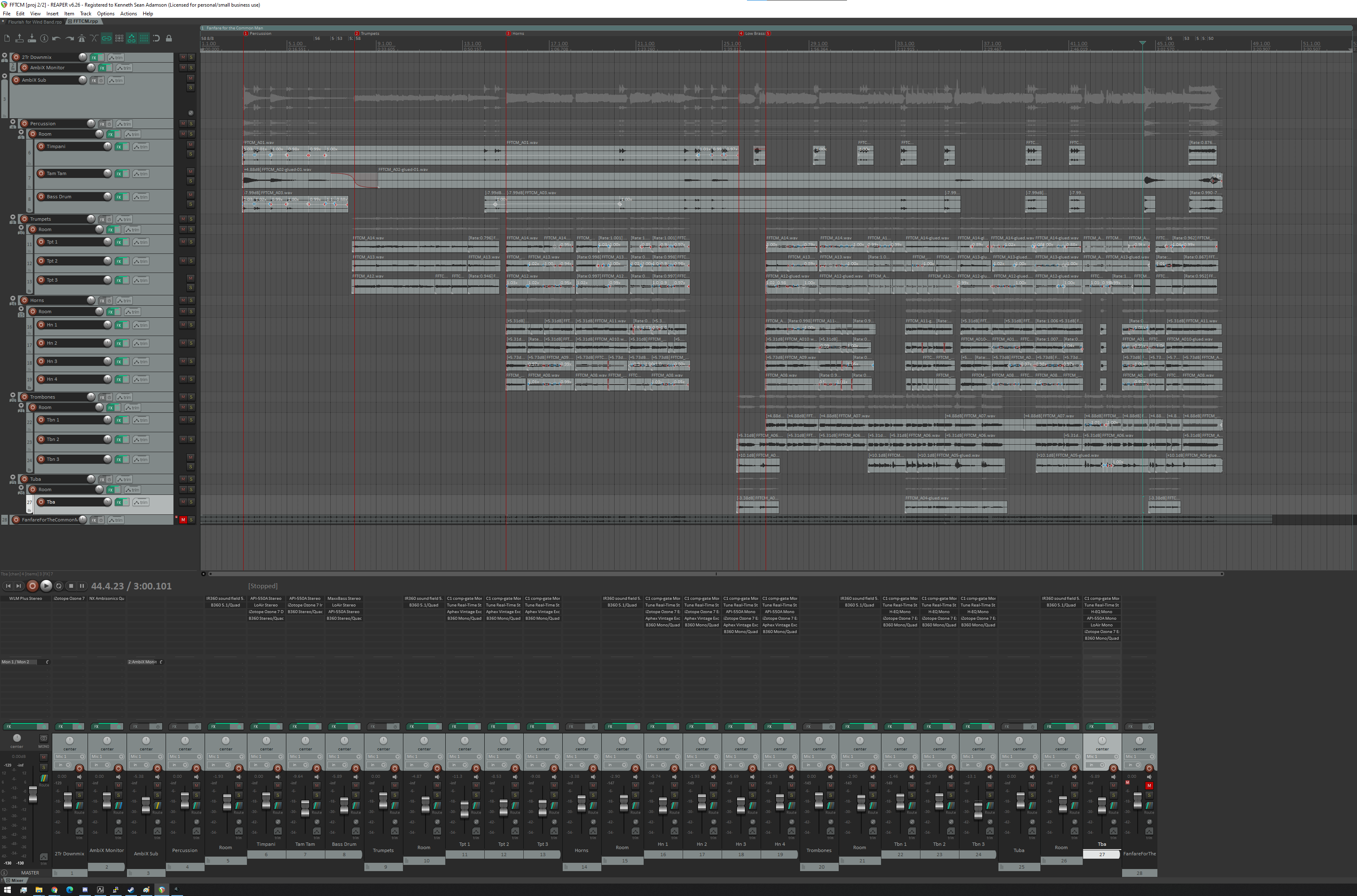

Ken: For the audio, 15 to 30 hours. Dave extracts the audio from the videos that are sent to him. I’m not exactly sure the extent of what the other guys do. I know that what I get has the first notes and the last notes lined up. All the stems (basic tracks) are the right length, and he just sends me a stack of files that are just 1 per instrument. They start at the same time and end at the same time. It takes 20-30 minutes per track just to place in the software on the grid. I mean that’s a few hours of work right there just to get everything lined up.

Fanfare for the Common Man was around 16 tracks and was fairly fast going. As a horn player, I’m already quite familiar with the piece. There’s not a lot of noodley fast moving parts going on. It’s mostly quarter notes, half notes whole notes stuff. It’s all about the texture. And the percussion is so critical in Fanfare.

With the click track, I then go about making very fine adjustments – in a non-destructive way – to individual notes to get everybody even more lined up and starting and stopping together. I take care not to make it “perfect”. The software I use could, in fact, make it absolutely flawless – but that sounds bad and artificial.

Mixing takes about a half day, including timbre corrections and setting the group into a “real” virtual space together.

For a concert, it is mostly a mastering job. I know we have a sound that I go for, and Jim trusts my ear and my aesthetic. I used to have to do a lot of back and forth. I would master track and then I would upload and share it with Jim, and he’d give me his feedback. As the years have gone on, he’s done less and less of that, where I just put it out.

KCO: I love that Jim has learned to trust people if for no other reason, then it’s just a way to divide the labor.

Ken: Mastering takes a lot of focus and absolute quiet in the house. The entire process usually takes a day to three of focused work for a single song.

Being part of the group, I want the music in as best a light as possible. My goal is for it to sound to other people the way I hear it in my heart. When we play something like Bruckner 4th Symphony or Shostakovich 12, I know those pieces. I know how I want them to sound. I know how I hear them at the concert, and my goal is to present a finished product to make other people feel the same way that I did.

With these virtual recordings, you have a lot of control because you have a single person’s isolated recording and there is the temptation to go and fix everything. To make it as flawless as possible. That’s great and all, but at what point is it no longer the same group? You’re essentially remixed and remastered it to death. In a sense, it’s not really the KCO anymore.

I don’t want to turn our recordings into something that you can produce in software with an orchestral library. I do a lot of eyeballing whenever I line it up beats and things like that rather than using the exact start of the waveform because I know that I’m going to introduce a little bit of error. It stays a lot more organic sounding.

Like I said before, I look at it as difference between a live recording and a studio recording. There is a lot more that can be done with a live recording than people realize. There’s amazing software out there that is actually capable of subtracting a bad note out.

After a concert, I’ve had people come up to me and say, “so you heard me flub my entrance? Do you think you could fix it?” I will give it a shot. I’m taking care to preserve someone’s dignity and it helps the overall product without being too ham-handed with the mix.

With a studio recording, you either trust your studio engineer or you don’t. I had a conversation with David Spangler. We’re talking about how far do you go with production to make these videos look as good as possible and sound as good as possible? And I said that I’m treating it like a studio session, so I’m going to do everything that I can, short of making it sound like sampled, orchestral music. He said that was good because these videos are going to be permanently in the world now. We need to treat them as well as we can. Dave and I are in the same camp.

KCO: In a project like this, what is something that people just don’t expect?

Ken: I try to work in highest fidelity domain as possible. I mean that I actually have photos of the orchestra that I’ve taken. I have measurements provided to me, by Jim, of our footprint. And I’m able to reproduce, physically, a sound stage from that. I do it in hi-channel surround sound or what’s called Ambisonic format.

I’m working in sometimes seven, eight up to 13 channel virtual audio for some of these projects. That’s a high-end film technique, but I’m a big fan of film music. I love me some John Williams and Alan Silvestri. Ben Hur, that’s one of the best soundtracks ever and they were working with monaural sound (mono).

I’ve even started working in Virtual Reality (VR). I’ve got my Oculus Quest 2 (VR headset) here and I’ve got some software that actually allows me to grab an instrument and place somewhere: like cellos stage left, violins stage right, violas in a spot, brass in the back, and woodwinds in the middle.

That’s how I mixed Fanfare for the Common Man. I watched several YouTube videos on different brass sections of different, famous orchestras. I saw how they were laid out. The one that struck me as best sounding in terms of the depth was Berlin. We are laid out in Fanfare for the Common Man in the same relative positioning as a video that I found of the Berlin Philharmonic brass section playing Fanfare.

KCO: Wow. that’s cool.

Ken: And it all gets played into this virtual environment. And what I have is, peoples’ recordings from their living room, and their closets, and their bedrooms. You have to make it sound like something other than recording in a bedroom. I picked St. John’s Basilica as one of the reverbs that I used.

I took some measurements of the chapel at Northwestern University and the primary reverb is this chapel but with the tails turned way up, so it has a nice deep long, lush reverb to it. This isn’t just panning left and right, which is all the control you have with an analog board like that, but actually placing sounds in three-dimensional space. Not Just X and Z, but also on a rake.

If you think about it, if you’re in a balcony, looking down at an orchestra, by your perspective, they’re at an angle, right? And that all makes it sound differently, particularly top firing instruments like the tuba. With a steeper angle, you get the more of the high-frequency material. You hear the lip sounds and overtones and everything. It really helps you blend better with trombones and horns and everything.

I spent some time over the last couple of years, diving deep into modern film score mixing and mastering techniques. I’m starting to use that for rather more mundane projects than scoring a film, but no less rewarding. I think that it’s turned out to be a really cool approach and set of tools for realizing projects like this.

KCO: It’s awesome. Well, thank you very much.

Thanks to Ken for the interview on 6 May 2021.

by Francis X. Langlois – tuba player in the KCO