Our third and final interview with one of the virtual concert creators is with David Spangler. In addition to the KCO, David plays with Puget Brass and Woodinville Community Band. David has also helped those groups with their video projects.

- Who are you and what do you play in the KCO?

- When did you start playing an instrument and describe your musical journey?

- How did you connect with the orchestra?

- How did you get started on the virtual projects?

- How many hours does it take to put together the video?

- What about this project is surprising to you?

KCO: Who are you? And what do you play in the orchestra?

David: My name is David Spangler. I play the trumpet, and I’ve played in the orchestra since 2003. It’s been quite a long run. I think all of that’s been with Jim (Truher) as the director/conductor.

KCO: Was there somebody before, Jim? I started in 2006.

David: There was somebody, I don’t remember the name of the person, but Jim was not the first director. Jim started around that time as well, as I understand. But somebody else actually started it.

KCO: When did you start playing an instrument and describe your musical journey?

David: When I was in fifth grade, I joined the Honolulu Boy Choir as a charter member and started singing. My mom had strongly suggested piano lessons, so I took piano lessons for two or three years when I was about eight or nine. That really wasn’t my thing. When I was in fifth grade, I picked up the trumpet. I liked it and kept going.

In intermediate school in seventh grade, the band teacher was a trumpet player. I started taking lessons with him. He was a great, great teacher and very, very calm. The kids loved him. It was really a family-type environment. Instead of eating lunch, I would go and practice. I played a lot. I really got started there.

I had a choice to attend ninth grade in the intermediate school or go to the high school. I stayed there in ninth grade and played, and we had a fantastic band. We played some hard pieces that were challenging. They made (vinyl) records of it! It was just a very positive experience. Mr. Matsumoto was the guy who made it a great experience.

Then, I went to Kalani High School for three years. I was first chair, pretty much through high school. We did marching band where I was the assistant drum major. The director told me he wanted me to be the assistant so I could play the trumpet solos for some of the pieces, which was fine with me.

I loved being in band and doing that. That was really it for me.

I went to college at the University of Hawaii and played my first year. I was in engineering school. I did a mechanical engineering undergraduate. The first year, I did the marching band and went to the football games. I was spending 25 or 30 hours a week in the marching band. We did a new show almost every week.

After the first semester, I realized that I can’t do this. I’ve got a lot of other classes to study for, and I just can’t spend this much time on band, even though it was a lot of fun. I pretty much gave it up.

After I got through college, I went to Stanford to get my Master’s. Then I came up here to work at Boeing and so I really didn’t play through those years. A few years later, I did play in the Boeing concert band for four or five years. I met a good friend of mine who lives right down the street from me. And that’s important, for reasons I’ll tell you in a second.

In the mid- or early 90s, Boeing and the industry went through a downturn. Morale was bad. I left there to do some consulting and so didn’t play for a while. In 2001 or so, I was doing some consulting at Microsoft and that turned into a full-time gig at Microsoft. That’s around when I start playing with the orchestra.

A little earlier, I started playing with Puget Brass, too. All of a sudden, I’m playing again. Anita (clarinet player in the KCO and David’s spouse) was in a choir. She heard this brass band rehearsing next door to where the choir was rehearsing. The guy I mentioned, who had played in the Boeing concert band, was playing in Puget Brass. That person is Chuck Fleming.

I called him up and he said we have an opening right now because one of the cornet players is out on maternity leave. I subbed in the band, but I didn’t have a cornet at the time. I bought one from Matt Stoecker (KCO trombone). They put me in the solo cornet row, that’s the front row of a brass band. I asked if any of these other people want to move to the solo cornet row (like first trumpet)? And he said, “no, they are good where they are.” That was my introduction to Puget Brass, which is a British-style brass band.

Chuck is a great player. He’s also a very social guy and so he likes to talk “a little” to people. I started playing and I’ve been with them ever since. It’s been 13 or 14 years of fun.

I’ve played everything from flugelhorn to solo, 2nd and 3rd cornet. I just play wherever they need me. That’s been a great experience. I grew up in wind band tradition. Playing with the orchestra was a different modality. I hadn’t really played with strings before. We had an orchestra in the schools, but we never played with them. So playing with the then Microsoft orchestra was interesting because it’s a different use of the trumpet.

The reason I’m still in the three groups — KCO, Puget Brass, and Woodinville Community Band — is because they’re all very different. I also subbed in a little bit in some jazz bands over the years. Right now, I’m subbing in a jazz band. The Solid Gold Hits group as the lead trumpet, but I don’t consider myself a lead trumpet player which is interesting. Most trumpet players have that really type A personality.

KCO: When I first met the trumpets in the orchestra, I thought these guys aren’t like the other trumpet players I know. They’re actually a little bit humble. What’s going on? But I adjusted.

David: Exactly. I get it. I understand the stereotype and that’s just not me. I’m more of a kind of a support. I’m just not a Type A person.

The Puget Brass band is how I got started on the videos. I’ve made six videos now with Puget Brass and Chuck participated in several those. It’s been hard to get people to engage. Some people are not interested in the virtual thing and recording themselves. I know several people like that. Or their living situation doesn’t really allow it.

I’m on the board for two of the groups, and both boards are asking how do we keep people engaged and prevent members from leaving?

One of my biggest fears was that if we didn’t play for a while, and it has been over a year, that people would say I’m done. Then, hang it up. We’d be back to square one and not able to play some of the more challenging, more fun pieces.

KCO: How did you connect with the orchestra?

David: I was working at Microsoft and the orchestra was rehearsing on campus. I just heard about it through some news groups at Microsoft. They had clubs back then and “hey, they have a music club? Great!”

I went to audition but they said, just come and play. It’s been a great experience, a big learning experience. Now I have a “C” trumpet. I got one because I was playing an orchestra. There were a lot of pieces where the first trumpet is in C D and even F.

I got to play a bass trumpet, which is kind of cool. We did a Vaughan Willams piece, and that was very interesting. You were there when I played the thing. Matt Stoecker brought it in. It had a bigger mouthpiece. I said, “wow, this feels like playing a tuba mouthpiece” and you said, “What’s wrong with that?” (laughter) That was awesome.

KCO: How did you get started on the virtual projects?

KCO: I can’t imagine you were just like making video projects before.

David: No, I had not done anything. When COVID hit, we were in the process of preparing for concerts for multiple groups. On the board, we decided we just can’t meet anymore because of COVID. That was a bummer.

I have an “adopted” sister, JoAnn, who is from New Jersey. JoAnn would go to Hawaii because she won the second trumpet position in the Hawaii Symphony during the orchestra season. In Hawaii, she was staying with one of the cellists in the community orchestra that my mom plays in. My mom plays cello. Something happened with her living situation so my mom said to JoAnn, “hey, I’ve got a room” so she was staying with my mom.

KCO: So, how did you meet her?

David: I was talking to mom who said we have a trumpet player staying here.

JoAnn is big-time and she’s become a really good friend. I mention that because we were chatting at one point and she said, “hey David, you want to play a duet?” Naturally, I said yes to this professional trumpet player. She had used this app called Acapella. She played her track and sent it to me. I played mine and it worked out well for a duet. I thought that was kind of cool.

During the pandemic, the board for Puget Brass started talking about what are we going to do? I told them about Acapella app. We decided to try it. We picked a piece called Deep Harmony, a tonal thing, that’s very, very slow. We use it for warm-ups. I figured we could use that because there’s not a lot of notes and it’s a good start.

We tried it but there were several limitations. You can only have nine tracks total. The coordination was complicated, and if you have one person that was delayed at all, everything just stopped. It took us three or four weeks to get that first recording. That was a very simple piece so I said, we could only have nine people and the end result was decent.

The other limitation is you only get one shot at it. If it didn’t work, you could record it again and again. But, you had to record it all in one take. For a short piece like this, each part is a about a minute and a half. For a more complex pieces, that was a non-starter.

That was our first attempt, and it was frustrating. It took a long time. There was minimal editing you could do. I had seen what some of these professional orchestras from Europe were doing, and they had 20 or 30 tracks. That’s obviously cool, but I also knew that it’s a lot of work. Having been in software pretty much my whole career, I knew there’s some effort there. Little did I know.

I decided I’m going to learn this and figure it out, so I did some research. I found a program called DaVinci Resolve. We created a click track and sent it out. Then I came up with the rules about how we’re going to do this. I just got started doing it. That was in March of 2020.

I decided I’m going to learn this and figure it out, so I did some research. I found a program called DaVinci Resolve. We created a click track and sent it out. Then I came up with the rules about how we’re going to do this. I just got started doing it. That was in March of 2020.

DaVinci Resolve had a free version. I didn’t really have to invest anything to get started. I found out it was a really powerful piece of software that motion picture studios use. If that’s if it’s good enough for them, it has everything that I would need, right?

I figured it out, and started putting the videos in. The first video we did in the Puget Brass, the result was really good. I obviously put in some time because I had a learning curve, but it turned out well. The lead cornet player, Matt Dalton, commented after we released the video, “that was way better than I thought we could do.” He knew how much work it would be to get everybody to sound good and be together. A lot of our members are not used to the studio musician mentality of playing with the click track or sync-ing with other people remotely, in a studio setting. This was the first time most people had done that. And it’s so different musically.

Plus, you’re recording yourself and you’re listening back to yourself thinking that sounds bad. That experience was foreign a lot of people in my groups. We’re not used to it. On the other hand, many high level musicians know it’s very important if you really want to improve.

The good news is that we’ve had enough engagement that we’ve been able to keep things going. So that part has been great.

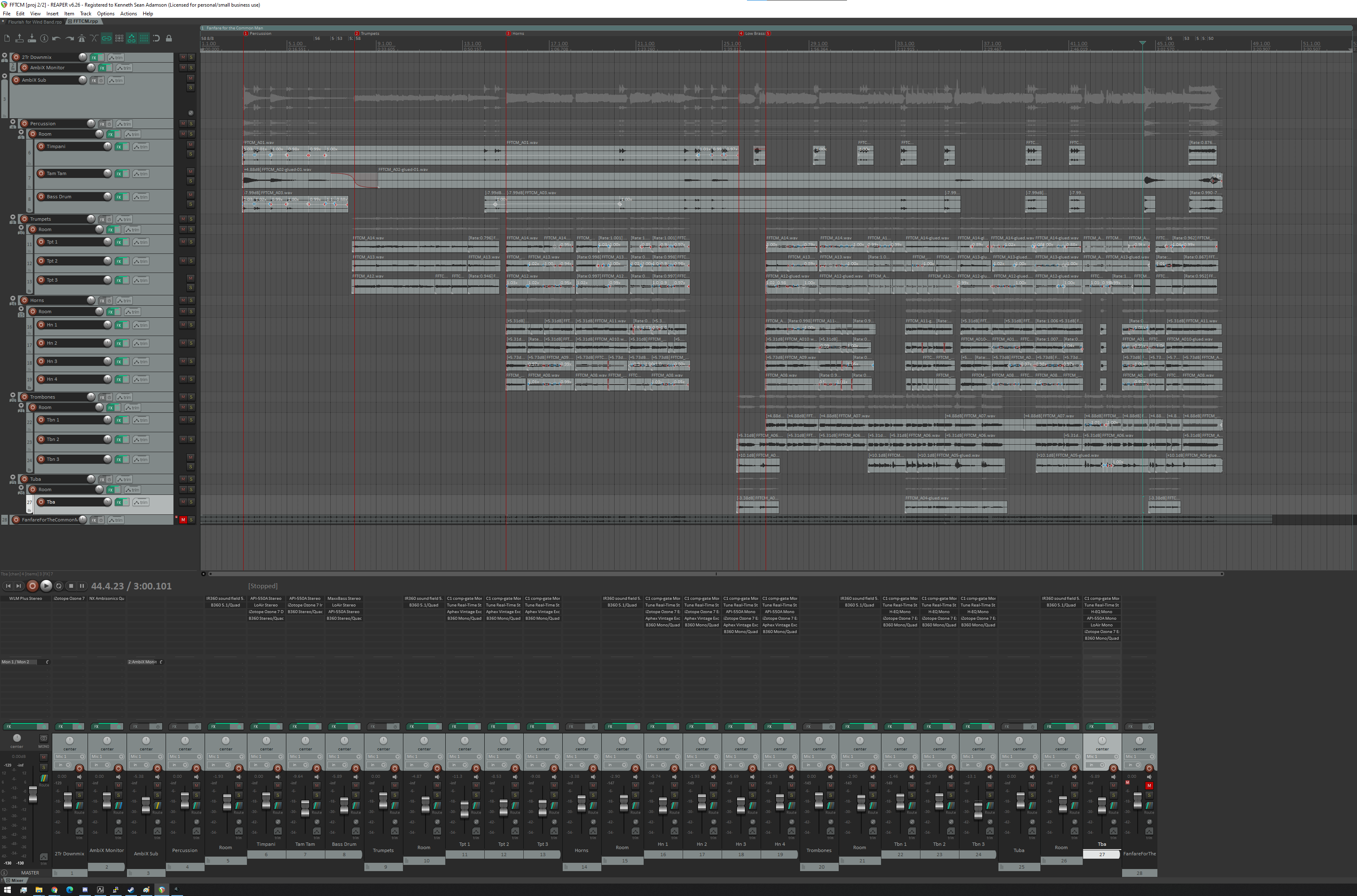

When we did Sleigh Ride, I had 53 tracks in that video. That was the most I’ve had to had to deal with and that’s a lot of data. But it’s a big data set to learn from.

I learned a couple interesting things. One is that a lot of the players had a difficult time with the metronome and the time especially offbeats. It was difficult to line things up. I developed a process for how I would do this. One of the things I look for in a music video is: does the video sync with what you’re hearing? It’s a pet peeve of mine when it doesn’t sync up. My process is to lineup everything in the time-space. I’ll line everything up, including the video and audio, keeping them together to do all the cuts together. Then I’ll combine it into a single track in that time space. Then I’ll work on the video aspect of it.

Really, I do the audio part first so it’s clean and then I’ll do some post-processing on the audio as well, doing some mastering. As my friend Ron Cole says, “adding the talent” right to the audio to make it really sound good.

I took some sound engineering classes in the last eight months and that has helped a lot. I can understand some of the effects and more the art of how you actually make it sound good. How you cut out some of the unnecessary audio effects and make it sound better, better stereo bandwidth, etc. It’s been a total learning space. Every video I’ve done, I’ve learned something, .

KCO: You were just motivated to basically teach yourself this?

David: Yes. When we were talking to the Puget Brass board early on, we wanted to continue doing something and playing in some fashion, virtually, but how do we do it? I volunteered. You know what? I think this is important for us to do. I want to do it. I’m going to invest the time, and now I had the time because I had retired. I had the time and motivation to figure this out and learn it. And it’s come in handy.

KCO: Come in handy?!?! That’s an understatement, Dave. It’s fantastic!

David: Jim, our director, and the board are not going to compromise or put people in a position where they like feel like they have to come to rehearsal and then have somebody get sick. Jim and really everyone would feel so bad. So, they’re really playing it super safe.

KCO: How many hours does it take to put together the video?

KCO: Let’s use Sleigh Ride as an example. It’s about four minutes of music approximately. I know you sent some of the audio to Ken, and some of the parts Doug helped create. So just talk about your part of the process.

David: That’s a good question. In practice, this is what happens. The tracks come in over a period of time. I set up the template for the project, and then I bring in the tracks as they come in. So there is the calendar time of weeks. It’s much more than the working time. It can take probably three weeks in the calendar time from the time I start getting the project setup and track start coming in to completion.

There’s a period that gets intense. Not everyone is organized and gets tracks to me on time. So there is some wrangling to do. Once I get the tracks, then I can usually work like maybe four to five hours at a time before I need to take a break. I would say, all up, it’s between 30 to 40 hours, of time for a four-minute piece.

Early on, the first videos I did, the video took maybe two thirds of the time because that was the hard part. Some of the video controls were not there. About six to seven months ago, DaVinci Resolve had an update to version 17. In that version, they had a new control that’s called ‘collage,’ which is what I was doing. This control made it MUCH simpler to do. It really simplified because I didn’t have to do a lot of the masking and whole bunch of layering that took a lot of time.

With the new collage control, I could just set it up—boom, boom, boom—then resize each of the individual videos. Before, I had to figure out all the masking and background effects. It was a lot harder.

Now, it’s probably 50/50, maybe even 40/60 for the video. And it was 60% for the audio because I really want to spend time on the audio and get it just right. That takes a lot of time, making sure people are lined up vertically, in pitch, and horizontally, in time.

KCO: One of the things you said to me, you said, “these things last a long time. They are going to be out there a long time.”

David: They do, exactly right. When you’re performing it live, it goes out, the audience hears it and they generally remember the last note that you play in this or the first, but if you make a mistake, it goes out and it’s gone, unless of course, you’re recording it. Then that will persist for quite some time after the performance.

It seemed important, when we did Fanfare for the Common Man, getting that opening section solid when three trumpets are playing in unison for 15-16 bars. It has to be together or else, it’s bad. I would spend some time in those cases making it sound better.

A person submitted recording and said, “measure 52, I played the wrong note. You want me to record the whole thing again?” No that’s fine. I found that note, I cut that note and adjusted the pitch. It was off by a third. I just moved that note down a third, and it blended right in.

KCO: But that’s more work on you.

David: That’s a little bit more work, but if it could save somebody else having to re-record the whole thing and potentially make other challenges. Those types of things are not a problem, and I’ve learned the tool well now. That’s something super easy to do.

I had someone submit a track and I put it together with mine. I listened and thought, wow, that just doesn’t sound good. The track was flat but it was flat the whole way through, so I just adjusted him up like 25 cents and then it was fine. I asked the person about it later. “Oh. Right. I forgot to tune when I recorded.” Oh well, that would explain it!

KCO: What about this project is surprising to you?

David: I have a new-found respect for the people that do the audio engineering and recording. And the professional videographers.

To be clear, I knew it was going to be a bunch of work and now I know it’s a lot of work. But I also know it’s doable. Before, I had no idea. When you don’t know, it could be it’s like ten or ten thousand, right? I now know it’s a lot of work but it is manageable.

You have to learn and understand the tool. I’m there now instead of having to research and figure out how to do everything. Just getting familiar with the tool and coming up with a process I could consistently reproduce. I then knew, in my own head, where we are in the project. I could understand about how much more time I have left.

I did get a set of studio level speakers and that made a big difference when I was mixing the audio part because the speakers that I had initially were just the run-of-the-mill computer speakers. They really missed a lot. With the monitor speakers, I was able to hear what was actually there. I could then do the adjustment and fix for it. That was probably the biggest thing that made a difference.

Creating the click tracks was something I had to figure out. I wanted to create something that had the music because I heard a couple click tracks that were just the click. It’s hard if meter changes. It’s easy to get lost.

I got feedback that the click track was a little too soft relative to the sound that I’m hearing. I made the clicks much louder and that helped a lot, but adding MIDI music helped not only where we are in the piece but also with intonation. You need the music to adjust while you’re playing. You need to hear it or you’re not playing to anything except the click.

KCO: Go figure, the musicians around you matter.

David: Exactly. That’s the biggest piece: what’s missing is you don’t really have other people. It was surprising to learn how much you rely on those other cues and the other the people playing around you to play. Which also leads people to play too loud, I think.

But the whole nature of this music is a give and take, playing with a group, and how do I respond to them? And we’re all going to go through this thing together. That’s really kind of a missing element in here.

KCO: I agree. Dave, this was great. Thank you.

Thanks to David for the interview on 19 May 2021.

by Francis X. Langlois – tuba player in the KCO

I decided I’m going to learn this and figure it out, so I did some research. I found a program called DaVinci Resolve. We created a click track and sent it out. Then I came up with the rules about how we’re going to do this. I just got started doing it. That was in March of 2020.

I decided I’m going to learn this and figure it out, so I did some research. I found a program called DaVinci Resolve. We created a click track and sent it out. Then I came up with the rules about how we’re going to do this. I just got started doing it. That was in March of 2020.